How and why Japan can be an alternative to China in the Indo-Pacific

How and why Japan can be an alternative to China in the Indo-Pacific

WRITTEN BY KYOKO HATAKEYAMA

16 December 2022

Asia’s maritime security environment is beset by increasing uncertainty. China not only claims sovereignty in the South China Sea over reefs, uninhabited islands, and maritime territory within its ‘nine-dash line’, but is also strengthening its effective control to block coastal states from engaging in fishing and resource-based economic development. This behaviour is also being exhibited in the East China Sea, where Beijing has repeatedly attempted to enter the Senkaku Islands’ contiguous zones and territorial waters — which are under Japanese jurisdiction — by claiming sovereignty over the islands. Despite international criticism, China’s efforts to upend the status quo are intensifying.

The Chinese challenge does not only concern Japan but also the US and other like-minded states because its assertiveness implies a challenge to the US-led regional order. Japan is a beneficiary of this order and has long supported it as an ally by providing Official Development Assistance (ODA) to other Asian states. As Japan’s economy grew in the 1970s and 80s, its economic presence in the region loomed over the regional states due to its growing trade, ODA, and investment. The dramatic appreciation of the yen due to the Plaza Accord of 1985 further accelerated Tokyo’s economic advance into the region, encouraging Japanese companies to employ subcontractors in Asia in search of cheap labour. As a result, intra-regional trade between Japan and the Southeast Asian states increased, promoting regional integration.

However, while Japan was the world’s second-largest economy for a long time, it has found itself in a slump since its economic bubble burst in 1991. Although Japan’s stock prices surged and unemployment rates improved during the Shinzo Abe period (2012-2020) due to Abe’s signature economic policy, ‘Abenomics’, the Abe government failed to put Japan’s economy on the right track. Economic prospects still seem glum in 2022, due to continued weak domestic demand. Japan’s inability to revive its economy contrasts with China’s impressive economic growth. With China following a similar trajectory, Japan’s position as a leading high-tech state has been eroding, not only because of China’s rapid development but also because of that of other regional players such as South Korea and Taiwan.

China’s expanding influence in the region

The slowdown of Japan’s economy makes it difficult for Tokyo to play a role in underpinning the current US-led regional order as it used to. In contrast, China is very keen to use its economic muscle to fend off criticism about its assertiveness and expand its influence in the region. For instance, as part of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, China submitted a bid for a high-speed train project between Jakarta and Bandung in Indonesia in competition with Japan. Shockingly to Japan — the long-term largest donor of economic assistance for Indonesia — Indonesia chose China over Japan for the USD 5.5 billion project, partly because Beijing did not require funding from the Indonesian government. China has also provided economic assistance to Cambodia for infrastructure development projects, such as building a port, roads, and an express highway. Not surprisingly, Chinese debt accounts for the largest share of the bilateral debt Cambodia owes, which implies growing Chinese influence on the country. Cambodia has also approached several Pacific Island states and offered economic and technical assistance without attaching any political conditions. It successfully concluded a Security Pact with the Solomon Islands in April 2022, shocking the US, Australia, and New Zealand because this confirmed China’s growing reach in the region once more.

Moreover, since Japan has maintained a stable relationship with China — despite their territorial disputes — the region does not have to worry about backlash or anger from China just because they choose Japan over China.

In addition, China helped support the region during the high point of the COVID-19 crisis. It quickly provided Sinovac vaccines to Asian countries that were struggling to secure vaccines, offering more vaccines than COVAX, the international framework led by the WHO. China’s Sinovac provision to ASEAN countries amounted to 12 billion doses — 4.8 times that of COVAX —, accounting for 96 per cent of the administered vaccines in Cambodia and Indonesia as well as 89 per cent in Laos as of June 2021.

More importantly, China is the largest trading partner for most regional states, including Japan. Although the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) — an agreement promoting a high level of trade liberalisation — was regarded as a platform to counterbalance China’s growing economic influence internationally, the Donald Trump Administration withdrew from the negotiation. Japan and Australia were disappointed by this decision because they expected the TPP to be an agreement that would symbolise the United States’ commitment to the region. Although the TPP was salvaged by Japan and Australia and launched as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) in December 2018, the size of the agreement has fallen from one-third under the TPP to 15 per cent of world trade under the CPTPP. In contrast, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which includes China but not the US, entered into force in 2022. Although the RCEP is not as comprehensive as the TPP and does not require a high level of liberalisation, regional economic integration centred on China is likely to deepen in the coming years, bringing about economic benefits to its member states.

Japan as an alternative to China

Japan’s sluggish economy and the growing economic gap between China and Japan reduce Tokyo’s traditional sphere of influence. However, China is unlikely to expand its influence enough to establish a Sino-centric order. This is because Japan provides an alternative to China for the regional states concerned about Beijing’s coercive behaviour and alleged ‘debt trap’ diplomacy.

First, Japan has provided quality infrastructure projects to the region. Since 2015, Tokyo has emphasised the importance of high-quality infrastructure projects, which contrasts Chinese projects (many of which have been criticised for alleged corruption and unsustainability). The importance of quality and sustainable infrastructure projects has gained international endorsement and so Japan’s emphasis on quality infrastructure has been endorsed by the G20 Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment. While Tokyo’s decision-making is slow and its projects are not cheap, its fair, viable, and transparent projects are attractive alternatives in Asia. Japan has also held the presidency of the Asian Development Bank, which has long supported Asia’s infrastructure development, since its inauguration. Although the size of the fund Japan can employ is smaller than that of China, cooperation with like-minded states — for instance, through the Trilateral Partnership for Infrastructure Investment in the Indo-Pacific between Japan, the US, and Australia — will widen the regional states’ options. Amongst others, the three states decided to fund the construction of an undersea cable that connects Nauru, Kiribati, and the Federated States of Micronesia, to provide faster internet access to each of the countries.

Second, Japan has provided military assistance to the region since the 2010s. By revising a regulation in 2014 that long restricted Japan from providing defence equipment, the Japanese government embarked on providing military assistance to other states (if the assistance would promote international peace and stability). It concluded bilateral agreements for the provision of defence equipment with the Philippines (2016), Indonesia (2021), and Vietnam (2021), contributing to upgrading their military capabilities. For instance, Japan’s provision of patrol vessels to the Philippine Coast Guards (PCG) enabled them to patrol disputed areas in the South China Sea. Tokyo has also started providing capacity-building support to the region’s militaries and law enforcement institutions to deepen security ties between Japan and the recipient states and to help them defend their maritime areas. Such support will strengthen their capabilities to counter China’s unilateral claims in the maritime domain.

Third, Japan has provided strategic assistance in terms of security in the region. Japan’s assistance to Indonesia shows that it is the regional alternative to China. When Indonesian President Joko Widodo sent a request to Japan to invest in the Natuna islands — where Indonesia has a dispute with China — Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi responded by promising assistance to Natuna’s fisheries development and empowerment of Indonesia's maritime security agency. Although Japan’s presence and the development of the disputed area do not directly deter Chinese action, its support creates hurdles for China to take assertive action towards Indonesia.

Japan’s economy is waning. However, its various support ranging from economic to military assistance provides the region with alternatives. Moreover, since Japan has maintained a stable relationship with China — despite their territorial disputes — the region does not have to worry about backlash or anger from China just because they choose Japan over China. They have the alternative, namely, Japan, to both China and the US; this enables them to avoid being trapped in the confrontation between the two great powers.

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent that of the 9DASHLINE.com platform.

Author biography

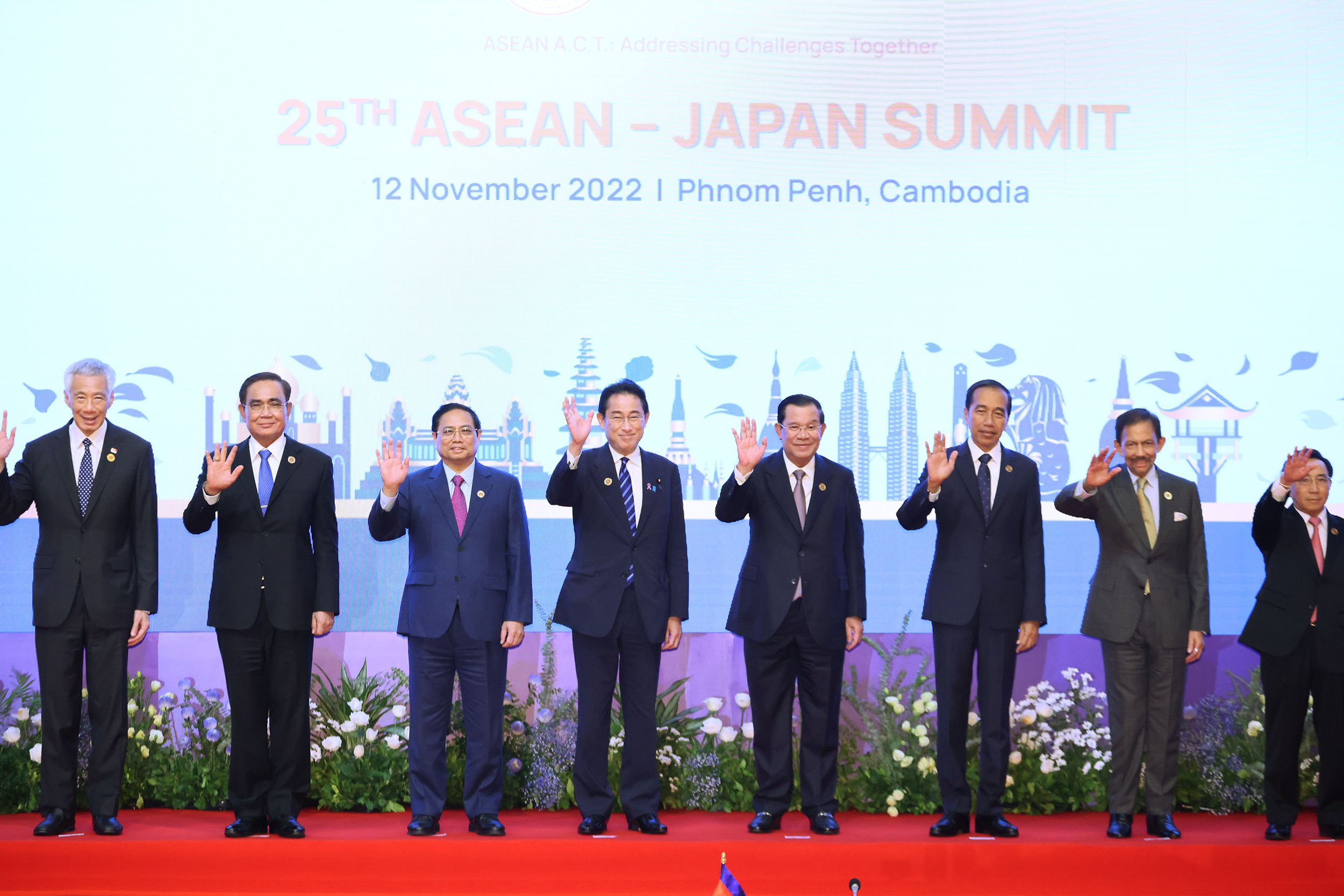

Kyoko Hatakeyama is Professor of International Relations at the Graduate School of the University of Niigata Prefecture. She is the author of Japan’s Evolving Security Policy: Militarisation within a Pacifist Tradition, Routledge, 2021. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/内閣官房内閣広報室.