The real reason Europe dislikes the Inflation Reduction Act

The real reason Europe dislikes

the Inflation Reduction Act

WRITTEN BY THIJS STEGEMAN

13 March 2023

The Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) USD 369 billion subsidy scheme is a big win for climate activists in the US, but it has put more strain on the US-EU relationship at a time when unity is imperative. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has pushed the two allies closer together after years of frustration. Trump (and other US presidents) complained often and loudly about European allies’ insufficient NATO contributions, slapped tariffs on steel and aluminium imports from the EU, and pulled out of the nuclear deal with Iran against the EU’s wishes. Under the Biden administration, the heated rhetoric has decreased, but Biden is still happy to use unilateral measures when he perceives his allies to be too ‘soft’. For example, US export restrictions on semiconductors against China have a significant impact on European industry as well. From this perspective, European frustrations with the IRA are just the latest in a long series of actions that threaten the unity of Western cooperation.

The goal of the IRA has been to speed up the energy transition by subsidising sustainable energy and technologies (i.e. electric vehicles, solar panels) and the legislation has been a major accomplishment in Biden’s political agenda. However, the IRA has generated accusations in Europe of unfair competition due to market-distorting government aid. In turn, American commentators frequently express their surprise at the European backlash. They emphasise that the EU had for years encouraged the US to adopt more environmentally sustainable policies; now that the US is doing so in the form of the IRA, the same European countries are criticising Washington for how these policies affect European manufacturing. American analysts generally dismiss these complaints as jealousy, by referring to the EU’s policy failures, or US exceptionalism: “when we do something, we do it big”.

Given the current challenges to the liberal order, improved coordination and consideration among its defenders is crucial. This starts with the US acknowledging and discussing the legitimate concerns of its allies instead of dismissing them.

Even if American commentators acknowledge that the IRA generates negative effects for the industry in the EU, they blame these side effects on the difficulties of getting the legislation through Congress: Senator Joe Manchin had negotiated details in secret, without allowing lobbyists or other senior Democrats to read them. Alternatively, these commentators argue that if the IRA poses an issue for Brussels, the EU should just set up a similar subsidy package. However, these dismissals hide the fact that the EU (and other US allies) raise several legitimate complaints that could have been avoided, and that increased subsidiarisation creates an unequal playing field for less wealthy countries. These are the real reasons Europe dislikes the IRA.

Competing approaches

At its core, the conflict over the IRA can be traced back to Brussels’ and Washington’s different approaches to the energy transition. Brussels has gained global influence as a standard setter — the famed ‘Brussels effect’ — and has for years been using a regulatory approach to rein in big polluters. For example, the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) permits major corporations to release a specific amount of CO2. They must purchase additional licenses, which are restricted, to go beyond their limit. As the annual number of licenses is reduced, the price of emissions rises. Despite criticism of its complex regulations such as the ETS, the benefit of this approach is that it ensures fair competition within and outside the EU. A product is treated equally irrespective of its origin if it meets the specified standards. This approach has the additional advantage of encouraging companies outside the EU to maintain higher-than-required standards for their domestic market. Although the regulation may make the EU less appealing to investors and exporters, its market size makes these standards impossible to ignore. Of course, the EU does not rely solely on regulation to drive its energy transition but also offers green subsidies; however, these are on a smaller scale and aim to avoid significant price increases.

Washington has taken a different approach. Owing to the domestic political difficulties of a 50:50 Senate at the time, the IRA does little in terms of regulating polluting industries. Instead, it aims to make sustainable products and industries more affordable relative to their polluting counterparts by offering subsidies like energy tax credits to attract producers. This approach has the dual advantage of reducing the cost of sustainable products and encouraging domestic manufacturing. It creates local jobs, shortens supply chains, and reduces external dependencies. The downside is that the subsidies attract a lot of green manufacturing and investments that otherwise would have taken place elsewhere. This means that, unless European and other countries offer competing subsidies, there is a real risk of deindustrialisation in Europe and flooding of the global market of subsidised American products. Ironically, these are the same practices that the US has accused China of, and they are likely in breach of WTO rules. US commentators have countered EU complaints by telling them to simply do the same. In the end, this could lead to an increasingly unequal competitive landscape, as not every country has the resources to provide subsidies of this magnitude. Certainly, the EU also provides industrial subsidies, but these comply with the fair competition regulations as established by the WTO.

In addition, the IRA has requirements regarding local content to apply for subsidies. For example, the IRA incentivises the purchase of electric vehicles through a USD 7,500 tax break, but this only applies if the car is produced in North America and its batteries are locally sourced. Comparable EU subsidies do not have such requirements. Rather, the EU again primarily relies on regulation, as it is banning the sale of all combustion engine cars by 2035. After French President Emmanuel Macron visited Washington in early December, Biden promised to “tweak” the legislation, but he remained vague as to what exactly would and could be done as the legislation had already passed Congress.

Moving forward

To be fair, there also are several areas where the US has valid complaints about the EU, especially in the realm of defence. The invasion of Ukraine has again illustrated how dependent Europe is on US military assistance, as European countries do not have the supplies to maintain the kind of industrial warfare that requires significantly more equipment and ammunition than the relatively limited missions NATO usually organises. As a result, European countries have become more open to a European pillar within NATO to handle security issues more independently and offer more support for American-led missions. The EU should face its own shortcomings at the same time as criticising the US about the IRA.

The EU needs to acknowledge that for the US, the IRA is a big step towards meeting its climate goals. With its implementation, by 2030, US CO2 emissions will have been reduced by 42 per cent compared to 2005, just short of its climate goal of a 50 per cent reduction. However, the legislation also poses yet another challenge to transatlantic unity. Unilateral actions and lack of bilateral consideration have put unnecessary additional strain on US-EU unity. The Trade and Technology Council was established to increase collaboration and smooth out differences. However, so far, the US has not taken its allies’ frustrations regarding the IRA seriously. Given the current challenges to the liberal order, improved coordination and consideration among its defenders is crucial. This starts with the US acknowledging and discussing the legitimate concerns of its allies instead of dismissing them.

The EU needs to increase its green subsidies and the EU Commission has already announced a ‘Green Deal Industrial Plan’. Nonetheless, the US needs to find a technical solution regarding its local content requirements. The invasion of Ukraine reinvigorated the EU-US alliance, helping both sides to temporarily overcome their difficulties. However, to step up competition with China and defend the liberal order, complete deglobalisation or protectionism as in the IRA is not the answer, as neither the US nor the EU currently possesses the capabilities to fight off all their challengers by themselves.

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent that of the 9DASHLINE.com platform.

Author biography

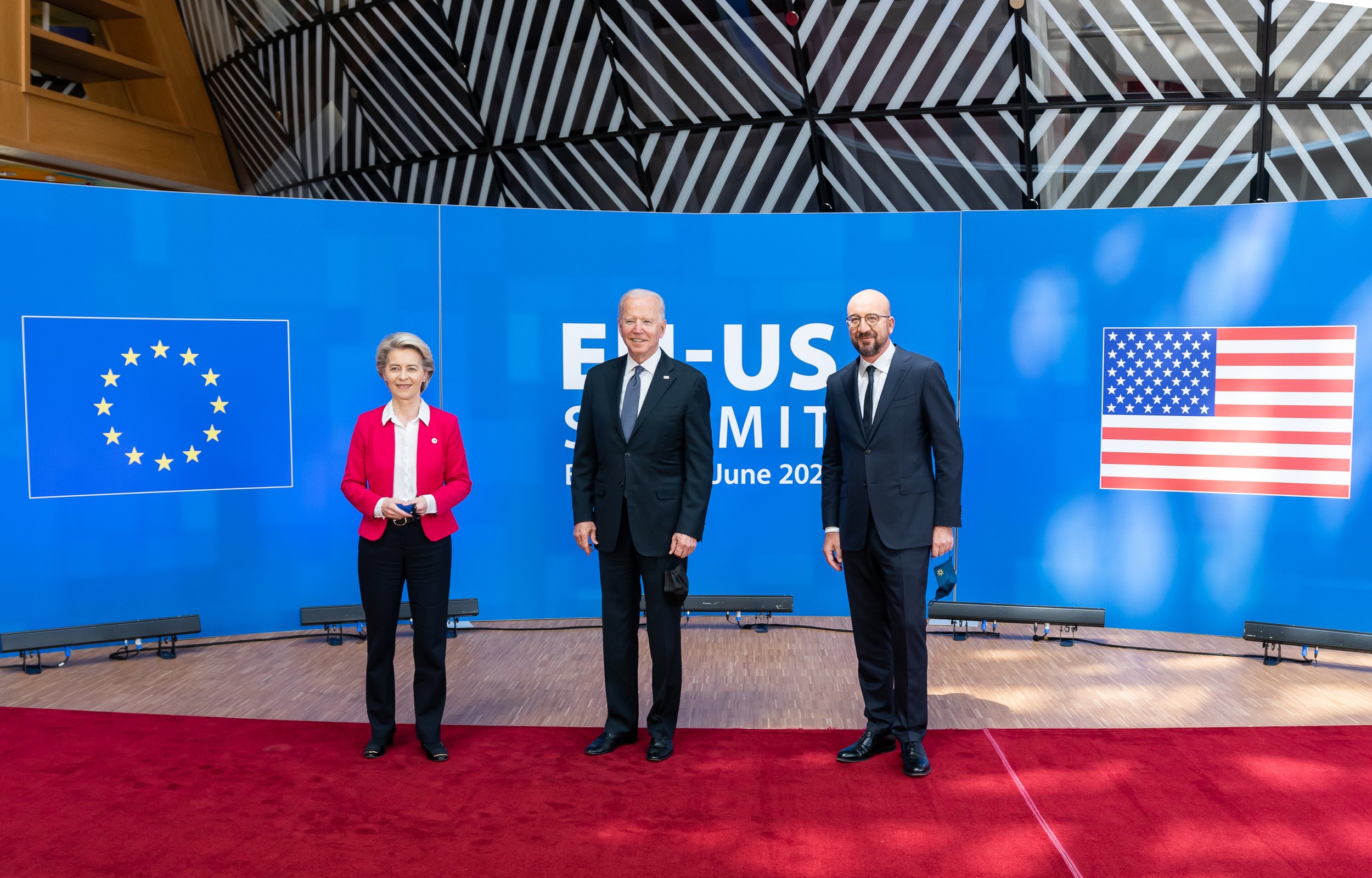

Thijs Stegeman is a PhD candidate at NDHU in Taiwan, specialised in Indo-Pacific politics. Image credit: Wikimedia Commons/The White House.