Bangladesh’s defence diversification and pivot to networked security

bangladesh’s DEFENCE DIVERSIFICATION

AND pivot to networked security

WRITTEN BY TAUFIQ E. FARUQUE AND RUBIAT SAIMUM

10 February 2026

Bangladesh is quietly pursuing a strategic reset in its foreign and defence policy following the fall of Sheikh Hasina’s regime amid the student-led uprising in July and August of 2024. This reset, initiated by the interim administration led by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus, reflects a shift away from an India-centric security posture towards a more flexible approach centred on military modernisation and diversifying external partnerships. For Bangladesh, strategic autonomy does not imply non-alignment, but rather the practical ability to make flexible decisions on defence procurement, military cooperation, and strategic connectivity beyond a South Asia–centric outlook. This shift indicates Bangladesh’s preference towards network-centric statecraft, which refers to the practice of advancing national interests by embedding oneself in overlapping diplomatic, economic, security, and institutional networks.

The post-2024 strategic reset

Under the ousted government of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh’s security and foreign policy were closely aligned with Indian priorities. Bangladesh supported India’s counter-insurgency efforts in northeastern states by handing over individuals linked to insurgent networks operating from Bangladeshi territory. At the same time, Bangladesh limited the presence of extra-regional actors in the Bay of Bengal and largely bandwagoned with India on key issues.

China’s presence in Bangladesh was politically circumscribed, focused on selective defence procurement — particularly naval platforms and infrastructure financing linked to the Belt and Road Initiative. Even so, Chinese engagement remained constrained by Indian sensitivities. This was most visible in Hasina’s shelving of Chinese-backed projects such as the Sonadia deep-sea port — which India viewed as a potential strategic vulnerability in the Bay of Bengal — and the Teesta River development project, located near the narrow Siliguri Corridor and likewise perceived by India as carrying strategic risks.

Bangladesh no longer intends to operate as a peripheral state within an India-centric security order in South Asia, but as a globally connected security actor seeking to maximise strategic autonomy over its procurement choices, maritime posture, and regional role.

This pattern reflected political dependency rather than strategic choice. Following Bangladesh’s one-sided 2014 election — boycotted by the main opposition party and weakening Hasina’s domestic and international legitimacy — Hasina relied heavily on Indian diplomatic backing to consolidate her hold on power and deflect mounting external criticism over democratic accountability and human rights violations. This reliance further reinforced deference to Indian preferences in defence partnerships and regional security cooperation, constraining Bangladesh’s flexibility in pursuing alternative security alignments. With the collapse of Hasina’s government in August 2024, this political dependency eroded. The removal of these constraints opened space for a multi-vector foreign policy posture under the interim government led by Chief Adviser Yunus.

Defence and military recalibration

The strategic awakening in Dhaka is most clearly visible in defence procurement and military diplomacy. Bangladesh has moved towards opening a Western combat-aviation channel, as the Bangladesh Air Force (BAF) signed a letter of intent with Italy’s Leonardo S.p.A. to purchase Eurofighter Typhoon jets. Additionally, Dhaka has reportedly approved a plan to acquire up to 20 Chinese J-10CE multirole jets at an estimated USD 2.2 billion — a package that would include training and sustainment arrangements anchoring long-term engagement with Chinese combat ecosystems. Bangladesh has also explored the potential acquisition of the jointly developed China–Pakistan JF-17 Thunder fighter, a lower-cost and rapidly deployable platform that would complement its evolving combat-aviation posture. Naval modernisation is also taking shape as reports indicate Bangladesh is in advanced negotiations with South Korea to acquire Improved Jang Bogo–class submarines, aimed at strengthening undersea capabilities. Dhaka has also expanded maritime diplomacy through a Bangladesh–Netherlands naval defence MoU, opening pathways for training, information exchange, and defence-industrial cooperation.

Beyond acquiring new platforms, Bangladesh is seeking to enhance domestic defence production capacity and acquire advanced technologies. In January 2026, the BAF signed an agreement with China Electronics Technology Group Corporation International to set up a drone manufacturing and assembly facility in Bangladesh, facilitating technology transfer, training, and workforce development. Bangladesh also signed a defence equipment and technology transfer agreement with Japan in February 2026, serving as a framework for acquiring advanced systems, conducting joint research and development, and expanding military expert exchanges.

The US remains a limited yet relevant security partner for Bangladesh, engaging primarily through joint exercises, maritime cooperation, and humanitarian assistance, but with a level of defence integration and industrial cooperation that remains narrower than the partnerships Dhaka is now cultivating elsewhere. Dhaka is opening new coordination forums and reviving previously constrained military channels, most notably through a Bangladesh–China–Pakistan trilateral mechanism committing the three sides to ongoing coordination and a joint working group. This follows Pakistan’s re-entry into Dhaka’s defence circle in 2025, marked by renewed high-level engagement — including Yunus’ meeting with Pakistan’s then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee in Dhaka — a largely absent interaction under the Hasina government, when defence ties with Pakistan were politically constrained. This renewed engagement has also extended into the maritime domain, with the Pakistan Navy chief’s visit coinciding with a port call by PNS Saif at Chattogram. Bangladesh is also exploring the possibility of sending its fighter pilots to Pakistan for advanced training — a move that would deepen interoperability around shared Chinese-origin combat aviation systems.

Bangladesh has also deepened engagement with Turkey, incorporating a major NATO member into its evolving security posture through defence-industrial cooperation and technology sharing. Bangladesh already uses Turkish-made Bayraktar TB2 unmanned aerial vehicles, a development closely watched in New Delhi and indicative of Ankara’s growing presence within Dhaka’s defence architecture. Reports from late 2025 point to further interest in Turkish platforms, including T-129 ATAK attack helicopters and the SIPER long-range air-defence system.

Bangladesh’s recalibration is also driven by mounting security pressure along its southeastern frontier. Hosting over one million Rohingya refugees amid deepening instability in Myanmar’s neighbouring Rakhine State — now largely controlled by the Arakan Army rebel group — Dhaka confronts persistent spillover risks and humanitarian strain. In response, Bangladesh has begun to consider a more forward-looking approach that emphasises enhanced surveillance and preparedness. This shift marks a move away from a purely humanitarian containment policy towards a more integrated security posture for managing prolonged instability along its border with Myanmar.

These dynamics reflect a wider strategic recalibration: Bangladesh no longer intends to operate as a peripheral state within an India-centric security order in South Asia, but as a globally connected security actor seeking to maximise strategic autonomy over its procurement choices, maritime posture, and regional role. The country’s recent security moves point to a broader multi-partner strategy rather than dependence on any single country.

The upcoming election and the durability of strategic change

As Bangladesh approaches its general election on 12 February 2026 — the country’s first since Hasina’s ousting — the political landscape has become more competitive. Current surveys indicate that the centrist Bangladesh Nationalist Party is leading, while the Jamaat-e-Islami–led Islamist alliance is closing the gap. Jamaat and its partners, including the youth-led National Citizen Party, whose leadership played a central role in toppling the Hasina regime, are expected to retain substantial mobilised support. Regardless of the election outcome, any incoming government is likely to face sustained pressure from opposition forces to avoid a return to the Hasina-era security and foreign-policy approach, particularly on policies perceived as prioritising an India-centric agenda. This pressure reflects lingering political backlash linked to India’s backing of Hasina’s authoritarian rule and her self-imposed exile in India following the regime’s collapse in August 2024.

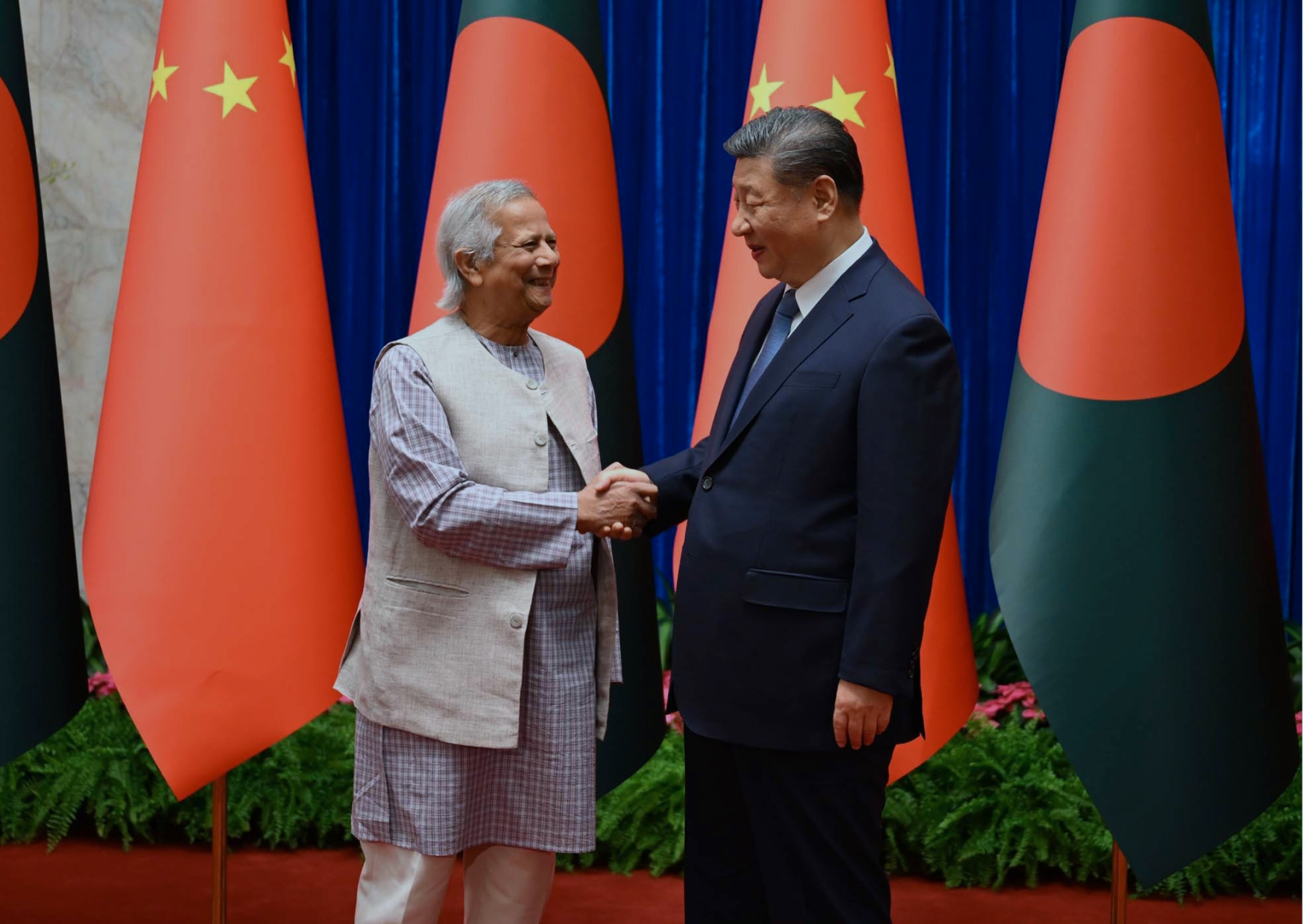

Chief Advisor Professor Muhammad Yunus meets with General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping at Beijing's Great Hall of the People - March 2025. Image credit: Press Information Dept/Wikipedia.

As Bangladesh moves into the post-election period, the next government is likely to build on the momentum generated under the Yunus administration’s multi-vector pivot and institutionalise it into a more durable, network-centric security posture, embedding Bangladesh within overlapping defence, logistics, and technology ecosystems. On this trajectory, Dhaka is likely to implement more structured cooperation with the US through practical frameworks such as the General Security of Military Information Agreement and the Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement. The Bangladesh–China–Pakistan trilateral working group is also likely to continue under this broader multi-vector approach. Given the changing circumstances, Bangladesh may also maintain, and even expand strategic commercial ties with China, including cooperation on the geopolitically critical Teesta River project, especially if no agreement on Teesta water sharing is reached with New Delhi.

Within the wider Indo-Pacific security context, Bangladesh is also seeking to expand maritime collaboration with Japan and Australia, drawing on their extensive experience in maritime governance and resilient coastal security. As the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation has become largely nonfunctional due to the persistent India–Pakistan rivalry, Dhaka is likely to deepen its eastward connectivity through a continued push for ASEAN membership, while maintaining its long-standing engagement with the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation. Together, these diverse alignments signal a new era of strategic autonomy for Dhaka. For Bangladesh’s global partners, welcoming this shift creates a new foundation for deeper cooperation, positioning the country as a resilient anchor for security in the Bay of Bengal and the broader Indo-Pacific.

Author biographies

Taufiq E. Faruque is a PhD student in Political Science at the University of Colorado Boulder, specializing in International Relations. His research examines security cooperation and armed conflict, with a regional focus on South and Southeast Asia and the strategic dynamics linking the two regions, particularly across the Bay of Bengal and the broader Indo-Pacific.

Rubiat Saimum is a graduate researcher at the Centre for International and Defence Policy (CIDP) and a PhD student in the Department of Political Studies at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario. Image credit: Unsplash/Saimum Islam Rumi.