Victory and sacrifice: The dual message behind China’s commemorations

Victory and Sacrifice: The Dual Message behind China’s Commemorations

WRITTEN BY VINCENT K. L. CHANG

29 September 2025

This month, China is observing two state-designated commemorative days, instituted in 2014 but only recently gaining wider global attention: Victory Day on 3 September, marking Japan’s 1945 defeat, and Martyrs’ Day on 30 September, honouring national sacrifice. A third follows later in the year, on 13 December: National Memorial Day for the Nanjing Massacre.

Long overlooked and frequently misinterpreted, these observances are often dismissed in Western commentary as little more than exercises in historical distortion or anti-Western posturing. That reading misses the mark. In reality, these commemorations are principally aimed at safeguarding what Beijing sees as the foundations of the post-war order and global peace. At the same time, they serve a sobering domestic function: preparing the public for sacrifice and endurance should those foundations erode and confrontation become unavoidable.

V-Day in context: China’s four gains from World War II

Two points of context are worth noting at the outset. First, China has commemorated World War II on this scale before — most notably with the 2015 military parade marking the 70th anniversary of Victory over Japan Day. It is also not unusual for the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) summit to convene in China with leaders such as Modi in attendance, as in 2018. What was new this year was the near-simultaneity of the two events, which amplified their symbolic weight.

Second, the absence of Western leaders at the Victory Day celebrations was not due to exclusion. As in 2015, Japan and the United States actively discouraged attendance. Trump may have hesitated, given his well-known interest in military parades and World War II heroism. Had political winds shifted, leaders such as Trump, Macron, Starmer, Merz, or Von der Leyen might have stood on the Tiananmen rostrum — echoing the optics of D-Day commemorations. Their decision not to attend instead signals a widening geopolitical divide, one that has little to do with the war’s history.

China and the United States should be willing to make concessions; treating compromises not as a sign of weakness, but as strategic wisdom. The rest of the world should ask what it can do to prevent escalation and avoid self-fulfilling threat perceptions, rather than contribute to them.

To grasp Beijing’s message, it is necessary to revisit what World War II represents for China. From its perspective, Victory Day marks four foundational gains. First, sovereignty was restored: Japan’s defeat ended eight years of occupation — fourteen in some regions — and fifty years of colonial rule in Taiwan. Chinese forces reclaimed Taiwan and key islands in the South China Sea with Washington’s help and acquiescence. Second, regional stability was secured: Japanese militarism was dismantled, war criminals were prosecuted, and Japan’s post-war constitution bound it to renounce war. Third, a new global order took shape, with China — initially bridging Nationalists and Communists — supporting the founding of the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions. Fourth, echoing Roosevelt’s vision of the Four Policemen, which cast China as Asia’s stabilising power, this order was designed to guarantee lasting peace.

World War II is thus seen in China as a decisive turning point in its modern history: ending a century of foreign intrusion and opening the path to national independence, regional security, economic prosperity, and lasting peace.

History repeated? The unmaking of post-war global order

Beijing now regards these post-war gains as unravelling, largely due to US actions. Global peace has come under strain, with armed conflicts at their highest level since World War II. The United States is viewed as an unreliable actor — instigator or catalyst — contributing to what Beijing calls the “root cause” of instability. The recent reinstatement of a “Ministry of War” is seen as emblematic of Washington’s strategic intent. Why else, Beijing asks, would the US Defence Secretary praise Japan’s “warrior ethos” — once the embodiment of America’s wartime enemy?

American interventions are increasingly seen as undermining multilateral institutions. The UN Security Council was bypassed during military actions in Iraq and Kosovo. In global trade, US unilateralism — through illegal tariff wars and the prolonged obstruction of the WTO appellate body — is interpreted as a regressive effort to dismantle the rules-based trading system that China helped shape and paid dearly to rejoin following its reform and opening-up. Securing WTO membership in 2001 took China 15 years of negotiations and considerable concessions, and it is not ready to see that hard-won achievement undermined by the very power that once championed the system’s creation.

Regionally, Beijing sees Washington — not itself — as the primary driver of militarisation. From the Quad Alliance in the Indo-Pacific to AUKUS and earlier THAAD deployments in South Korea, the US has expanded rather than reduced its military footprint across post-Cold War Asia. By contrast, China’s actions in the South China Sea are, in its view, defensive necessities rather than aggressive provocations: would Washington tolerate Chinese bases encircling the US mainland or militarising the “Gulf of America”?

The sharpest grievance remains sovereignty. Western involvement in or support for Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Taiwan — under the banner of democracy, rule of law, and human rights — is perceived as provocation and strategic containment. Increased arms sales to Taiwan, seen as contravening earlier bilateral Sino-US commitments, along with high-level visits such as Pelosi’s in 2022, are viewed as destabilising and insincere.

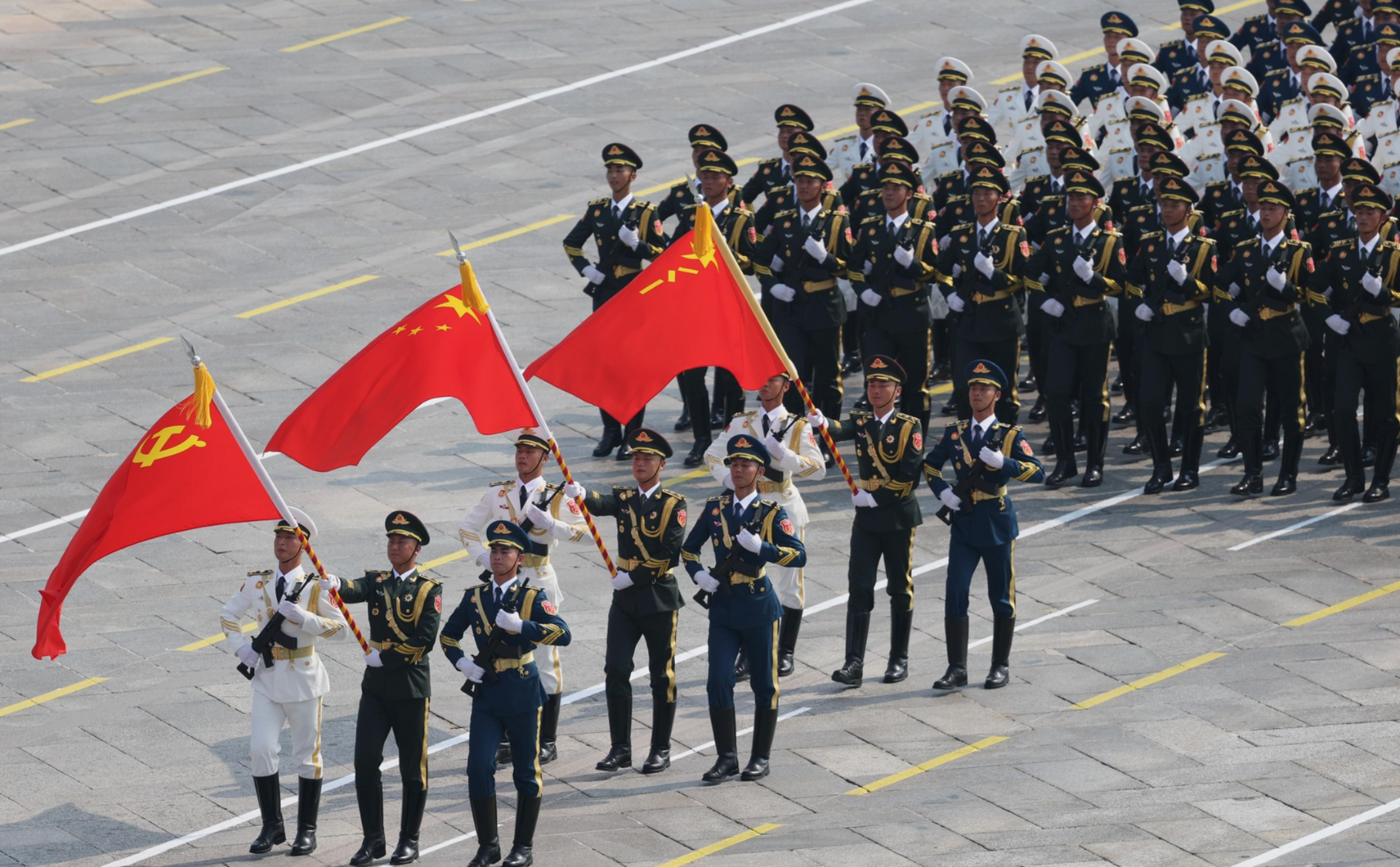

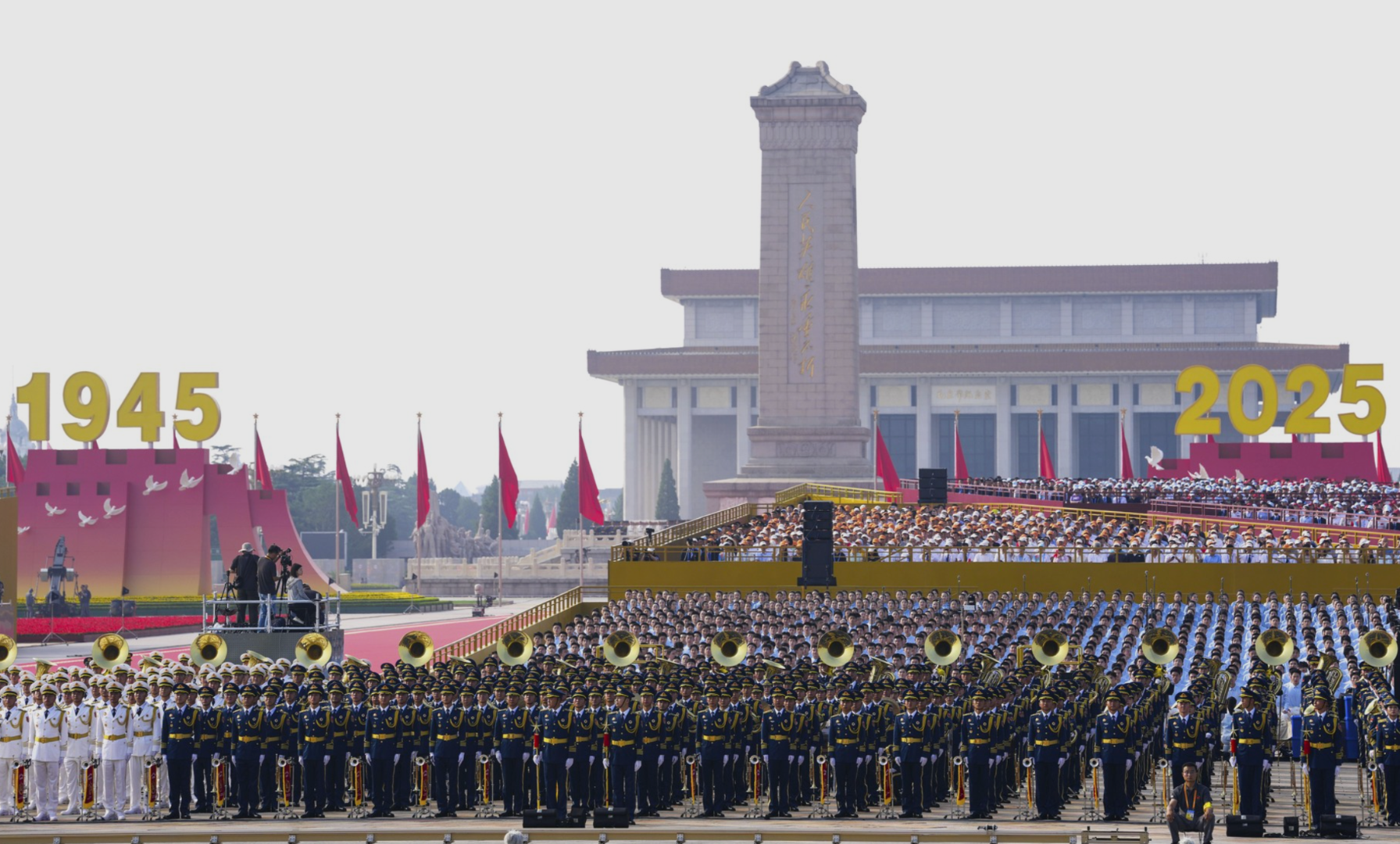

Military parade in Beijing to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II. Image credit: kremlin.ru

In Beijing’s view, these actions risk reviving the very conditions that led to World War II: global conflict supplanting peace, unilateralism overriding multilateralism, unchecked militarism in Asia, and the erosion of Chinese sovereignty. It is deeply concerned that US efforts to dismantle the global order echo the path of Imperial Japan — withdrawing from the League of Nations in 1933, embracing unilateral aggression, and mobilising and emboldening its strategic partners in pursuit of confrontation.

Beijing’s dual messaging: co-victors or co-victims?

In light of these concerns, Beijing’s message is the following: China will not cede ‘an inch’ of its sovereignty – whether in Taiwan or the South China Sea. The United States and its allies must stop disrupting and dividing the Indo-Pacific, and Washington should return to its role as guardian of the post-war order — helping to reaffirm, sustain, and modernise it. Global peace, for Beijing, demands an honest reckoning with history: remembering what caused World War II, and who did what to whom — something not only Pete Hegseth, but also the EU’s top diplomat, Kaja Kallas, has clearly failed to do.

Western observers interpreted the SCO summit as evidence that China and the Global South are pushing for a new global order. But from their perspective, the goal is the opposite: to restore multilateralism, sovereignty, and non-interference amid ongoing erosion. Defending the post-war global order, in this view, does not mean endorsing the Western myth of the “liberal order”, but rather reaffirming and updating the existing UN Charter-based system rooted in Roosevelt’s vision of peace. To underscore this, Beijing highlights its own record: it has not waged war since 1979 and today contributes more UN peacekeeping troops than any other permanent member of the Security Council.

Whether China’s leadership believes the West — especially the United States — can pivot towards cooperation or accommodation remains doubtful. Washington appears increasingly united across party lines in its resolve to obstruct China’s rise. The ideological framing of democracy versus autocracy is viewed in Beijing as a smokescreen — concealing strategic intent and consolidating Western alignment. Across China and much of the Global South, the US is seen as driven more by power preservation than democratic conviction, fuelling deep concern about the prospects for genuine dialogue or compromise.

Hence China’s preparation for the second track in its dual strategy: sacrifice and endurance. By reviving themes of heroism and martyrdom, Beijing is conditioning the public for hardship. Should conflict arise, citizens are expected to be ready to endure and sacrifice once again. That is why the heroes of the past — those who gave their lives for peace — and their contemporary successors are commemorated annually on Martyrs’ Day and on 13 December. These commemorations are not merely symbolic; they are integral to a broader campaign to cultivate national resolve, readiness, and loyalty to both party and state.

Strategic empathy: a narrowing window for coexistence

Beijing’s commemorations are selective and self-aggrandising, yet it is hardly unique in sanitising and essentialising its war remembrance. Rather than dismissing these rituals, we should look through them to discern the underlying message. That message combines aspirations of cooperation, which offer hope to the world, with red lines that it must at least understand.

Understanding Beijing’s perspective — and that of its Global South partners — is essential. Not to validate or accept their positions outright, but to grasp the motives, mindsets, and intentions that shape their actions, which can help to enable more effective engagement. China and the United States should be willing to make concessions; treating compromises not as a sign of weakness, but as strategic wisdom. The rest of the world should ask what it can do to prevent escalation and avoid self-fulfilling threat perceptions, rather than contribute to them.

Encouraging coexistence rather than conflict between great powers is not about choosing sides, endorsing ideologies, or indulging in rhetoric. It demands sustained effort, genuine engagement with the Global South, independent and imaginative diplomacy, and the capacity to see the world through the eyes of others. Commemorations are never solely about the past; they are a lens into the future. Whether that future is shaped by confrontation or cooperation depends not only on Beijing and Washington, but on the choices made by the wider international community.

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent that of the 9DASHLINE.com platform.

Author biography

Vincent K. L. Chang (PhD, LLM) is university lecturer at Leiden University and senior fellow at the Leiden Asia Centre. His research focuses on the history and global relations of modern China. He currently leads the international research project Advancing Authoritarian Memory: Global China’s New Heroes (2024–2027). Image credit: kremlin.ru.