Fair and balanced EU-India relations: what mutual benefit really requires

Fair and balanced EU-India relations: what mutual benefit really requires

WRITTEN BY STEFANIA BENAGLIA

20 December 2025

For years, EU–India relations have been described with a familiar refrain: “punching below their potential”. It has become a comfortable line for policymakers on both sides — a diplomatic acknowledgement that the partnership hasn’t delivered what it could. But few actually ask the harder question: what is this potential, and what would a genuinely fair, balanced, and mutually beneficial relationship even look like? And just as importantly: is that even possible?

Defining success is more complicated than repeating the familiar rhetoric of shared values and converging interests. As both Brussels and New Delhi navigate an increasingly fractured geopolitical landscape, the old narratives around “shared values” and “natural partners” are beginning to feel insufficient. The more honest description emerging today is that of a partnership “of necessity”. For some, that sounds pessimistic. In reality, it might just be the maturity the relationship needs.

Let’s start with the obvious: trust is low. Competing interests, diverging worldviews, different regulatory cultures, and misaligned expectations have all contributed. But low trust does not automatically mean weak potential. If anything, moving past the illusions and embracing realism creates space for a more pragmatic, durable, and honest partnership. Against this backdrop, the question of whether the EU and India can build “fair, balanced, and mutually beneficial” relations becomes both more complex and more urgent. The ambition is admirable, but can it be achieved?

This is where the Free Trade Agreement (FTA), an upgraded Trade and Technology Council (TTC), a potential Security and Defence Partnership, and the new roadmap expected at the 2026 Summit — all infused by a responsible and strategically aligned private sector — will be decisive.

The FTA: political signal or transformative tool?

The ongoing negotiation of the EU–India Free Trade Agreement is a central test of this ambition. Concluding the FTA would undoubtedly be a political milestone, signalling that the relationship is finally ready to move beyond rhetoric. However, it remains to be seen whether the FTA itself can be fair and transformative.

If the EU and India choose realism over rhetoric and build trust not only between governments but also among businesses, innovators, and people, the 2026 Summit could mark a genuine turning point — one where strategic clarity finally replaces political symbolism.

Although an FTA is widely seen as the cornerstone of the next phase of EU–India relations, the uncomfortable truth is that both sides will have to compromise — and do so visibly. India’s protectionist instincts remain strong; the EU, for once, is on the receiving end of difficult market-access conversations. This negotiation is like no other; here, the political externalities far outweigh the economic impact.

The latest EU Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment confirms that the FTA would not be a macroeconomic game-changer: a modest GDP gain of 0.1 to 0.2 per cent for the EU and 0.6 to 1 per cent for India. Rather, the real significance lies in a boost in bilateral trade volumes and a reinforcement of supply-chain diversification — both essential in today’s geopolitical climate. If combined with a new type of investment agreement, an FTA could increase export-oriented investment in India and boost its manufacturing sector. It would also signal that the EU is capable of pursuing a more strategic trade policy in the Indo-Pacific, one aligned with its broader geopolitical goals. In short: the FTA will not be a game changer for GDP, but it will be a game changer for politics.

More than anything, an FTA that is perceived as fair by both partners could help address the trust deficit that has long hindered progress. Trade is not merely about tariffs; it is about predictability, transparency, standards, and the confidence that businesses can operate without abrupt regulatory shifts. For the FTA to be truly impactful, it must address existing concerns and move beyond political symbolism, offering a genuine, rules-based instrument that strengthens the relationship through predictability and transparency, and thereby boosts business confidence.

Bringing the private sector In: the missing link

To bridge the trust gap, government-to-government dialogue will not be enough. People-to-people engagement — and especially bringing the private sector directly into strategic conversations — will be essential. Businesses understand operational bottlenecks, regulatory incoherence, and market-access challenges far better than political actors. As a result, they can provide the solutions the public sector cannot envisage. As long as the EU–India relationship keeps its G2G track separate from its B2B track, progress will remain slow and uneven.

The EU and India already have multiple strategic dialogues, but the private sector is still too often an afterthought rather than a partner, behaving more like a consumer than a responsible stakeholder. If the FTA is to be meaningful — if the TTC is to be revived and connectivity, technology, supply chains, and green-transition collaboration are supposed to scale — the private sector must sit at the same table as governments, and responsibly contribute to strategic decisions.

This is even more important now that the EU’s foreign policy is undergoing a structural shift. Public-sector-driven foreign policy belongs to the past. Through Global Gateway — the EU’s flagship initiative for building sustainable infrastructure through strengthened partnerships — the EU is moving from public-sector-driven cooperation to partnerships enabled by private capital, Return of Investment logic, blended finance, and strategic industrial policy. The business community — from big conglomerates to small and medium-sized enterprises — is no longer a peripheral actor; it is at the centre of the EU’s external engagement. This transformation is global, but nowhere is it more urgent than in EU–India relations.

The FTA negotiations — and, above all, the strategic partnership — cannot move forward without a private sector that acts as a responsible protagonist. The public sector increasingly recognises this reality; the challenge now is to bring the same level of awareness, strategy, and alignment to the private sector. EU–India relations will not be “mutually beneficial” unless the private sector is engaged early, and at a systemic level. A “fair, balanced, and mutually beneficial” relationship demands it.

The same logic applies to the Trade and Technology Council. The TTC has enormous potential but has so far underperformed. In theory, it should be one of the most promising tools for strategic alignment. In practice, it has underdelivered because India approaches it through dynamism, entrepreneurship, and rapid scaling, while Europe approaches technology through regulation, standard-setting, and risk management. These two models rarely meet.

The TTC needs a reboot — one that elevates industry as a co-architect, not a passive stakeholder. Technological sovereignty is now central to geopolitical power, and both sides increasingly understand the necessity of reducing over-reliance on the United States and China. A truly strategic TTC requires not only political alignment, but also practical cooperation driven by the companies that build and deploy technology.

Security and defence: the missing political anchor

The EU has recently developed a new tool in its external action toolkit: the Security and Defence Partnerships. Already launched with Japan and South Korea, these create a platform to deepen operational cooperation, build resilience, and coordinate on emerging threats. The planned Security and Defence partnership with India creates an important political bridge and helps reduce mistrust. It may also facilitate defence-industrial cooperation — a key step that would help India diversify its suppliers while enabling Europe to achieve the scale and cost-efficient production it needs.

But here, the elephant in the room is impossible to ignore: India’s relationship with Russia. Unless addressed candidly, progress will be limited. A fair partnership is not one where both sides agree on everything, but one where disagreements are understood, contextualised, and managed with transparency. Ultimately, achieving fairness and balance in EU–India relations is less about eliminating asymmetries and more about managing them transparently and meeting expectations.

The next EU–India summit in early 2026 will test whether both sides are ready to move in that direction. By then, three major developments are expected: the conclusion of the FTA negotiations, the adoption of a Security and Defence Partnership, and the unveiling of a new EU–India roadmap. The latter builds on the New strategic EU–India agenda: Council approves conclusions - Consilium and moves relations forward from the previous India–EU Strategic Partnership: A Roadmap to 2025.

So, can EU–India relations ever be fair, balanced, and mutually beneficial? Not perfectly — and certainly not symmetrically. But fairness does not require symmetry; it requires clarity of expectations, candid engagement, and the willingness to leverage differences rather than ignore them. As FTA negotiations approach a decisive phase, both sides must define what success truly means — through meaningful compromises, deeper private-sector strategic inclusion, a recalibrated Trade and Technology Council, and an honest approach to security cooperation, including the Russia question. If the EU and India choose realism over rhetoric and build trust not only between governments but also among businesses, innovators, and people, the 2026 Summit could mark a genuine turning point — one where strategic clarity finally replaces political symbolism.

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent those of the 9DASHLINE.com platform.

Author biography

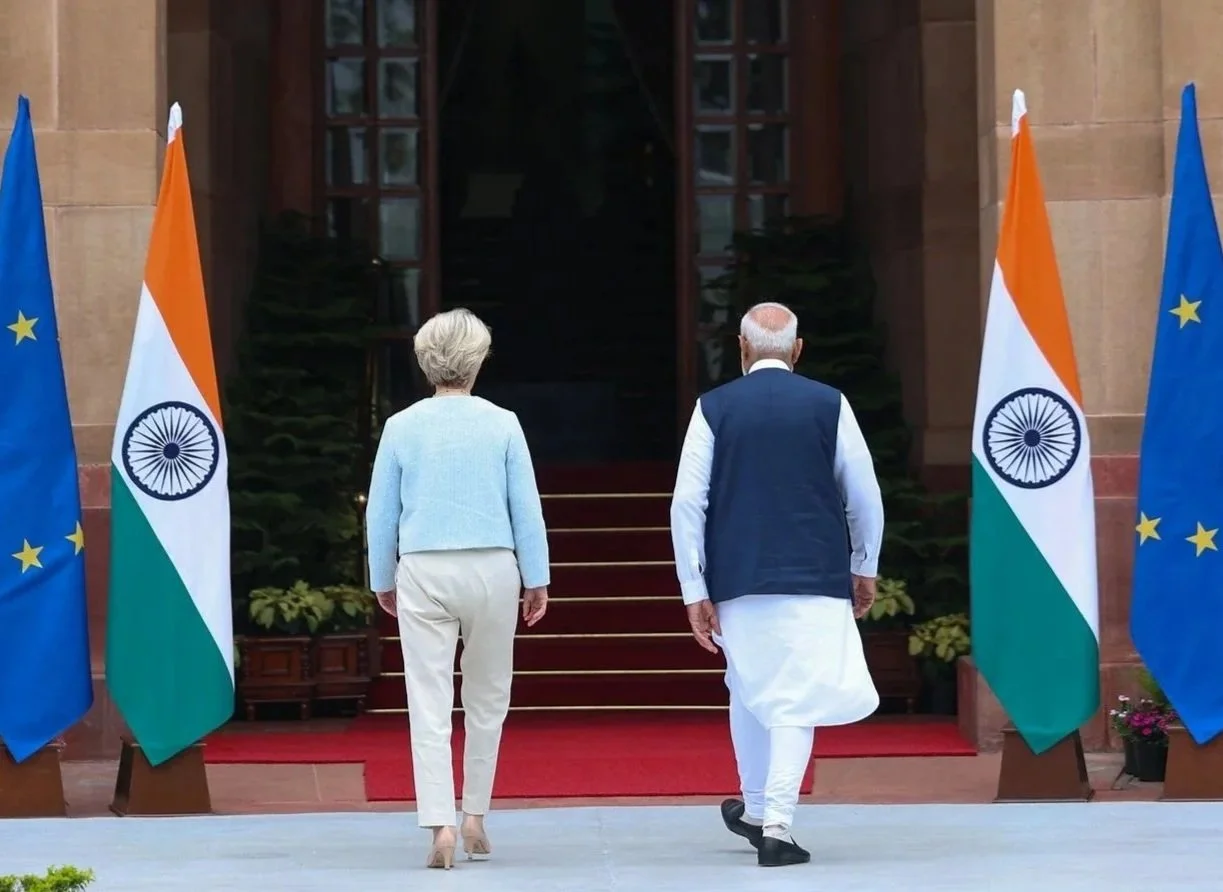

Stefania Benaglia is an EU foreign-policy expert specialising in EU–Asia relations and the Global Gateway. Based in Brussels, she advises public and private clients, and previously led Foreign Policy at CEPS. She has held positions at the European Commission and NATO Parliamentary Assembly, with experience in India, Israel, the US, France, and Spain. Image credit: Flickr/MEAphotogallery (cropped).