Europe's dependency on critical minerals: How China keeps EU industry on a tight leash

Europe’s dependency on critical minerals: How China Keeps EU Industry On a Tight Leash

WRITTEN BY KRISTOFERS KRUMINS

3 February 2026

Critical minerals and rare earth elements are increasingly crucial to the global economy, underpinning key sectors such as clean energy, digital infrastructure, and modern manufacturing. They are indispensable for producing high value-added technological goods, including electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, solar panels, data centres, smartphones, and even defence systems — which are all the more important in a world where states are increasingly vying for strategic autonomy.

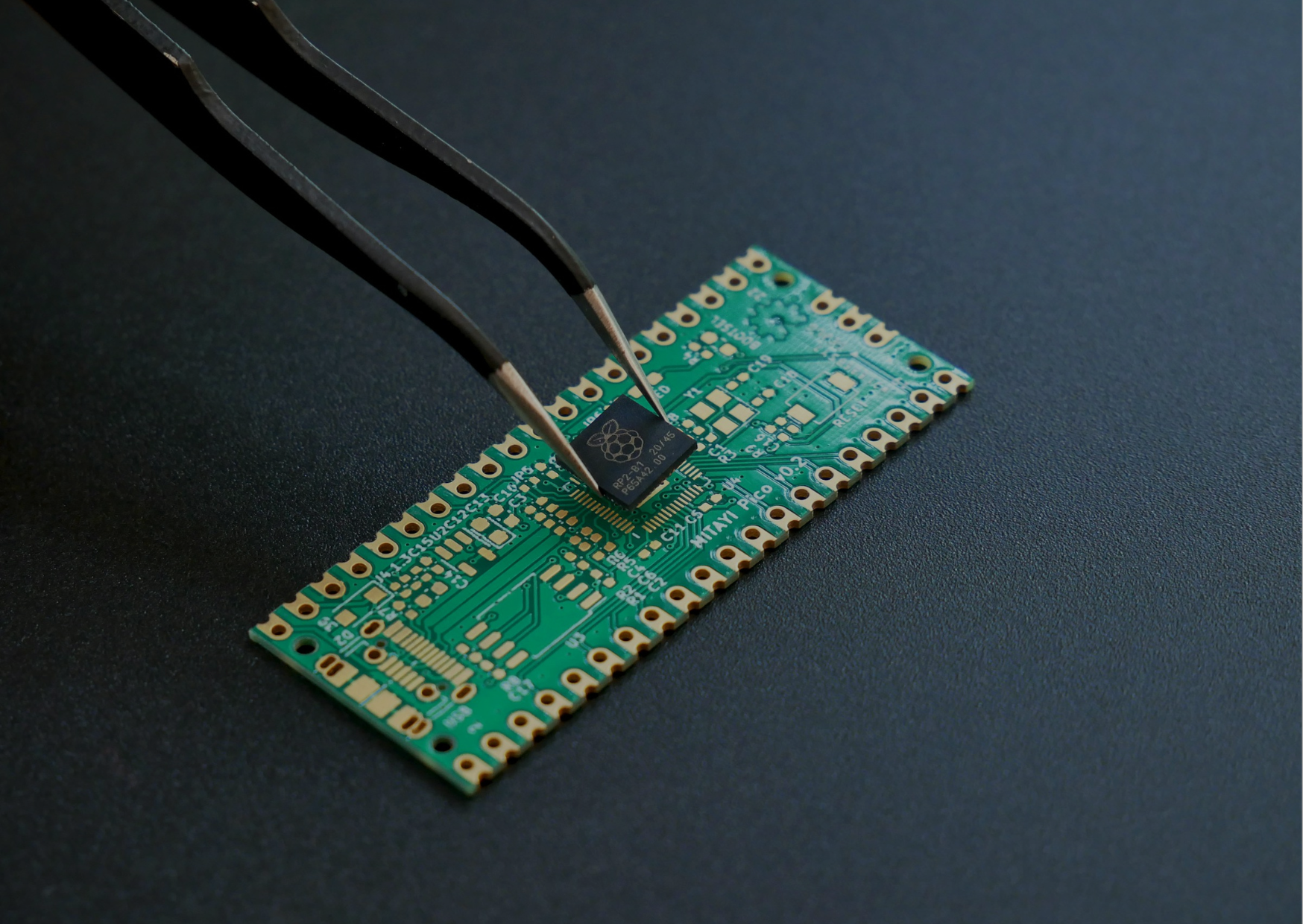

However, China’s chokehold on critical minerals and chips poses a serious problem to the European Union, especially given the bloc’s increasing internal rifts regarding foreign policy, trade, and larger divisions over the vision for Europe’s future. Today, the EU is heavily dependent on rare earths and key battery inputs. China supplies approximately 95 per cent of the EU’s imported rare earth elements and close to 65 per cent of critical raw materials. Likewise, China produces roughly 75 per cent of the world’s lithium-ion battery cell manufacturing capacity. Another crucial and often overlooked aspect is the geopolitical leverage China has quietly gained through its leadership in producing green technology, which the EU deems strategically vital. Be it Europe’s aim of strengthening its defence capabilities or ensuring it does not renege on its climate targets, China will remain a crucial player in the Union’s decision-making calculus.

However, in late September 2025, in an unusually tough move, the Dutch Economic Affairs Minister Vincent Karremans took control of Nexperia B.V — a Dutch subsidiary of the Chinese semiconductor manufacturer Wingtech Technology — saying the move was needed to prevent Wingtech's founder from moving company secrets and production to China. Karremans thus signalled his country’s resolve to avoid an adversary’s hold on the continent, in the sphere of critical minerals and chips manufacturing. After China retaliated on 4 October by limiting the supply of Nexperia’s chips, which are packaged in China, Karremans had to backtrack in fear over shortages in chips for many European car-makers.

China’s longstanding chokehold on Europe

The Dutch case provides a clear illustration of Europe’s problem when it comes to its trade policy with China. As with many other policy areas in the EU, without enough coordination within the bloc, unilateral measures are deemed to fail in face of a much bigger economic competitor like China. While there is a significant collective action problem in the EU in ensuring its strategic economic autonomy, it is not entirely bleak. It is up to the EU Commission to make a more concerted effort to encourage its member states to act in the continent’s long-term interests.

In a bid to power green and digital transitions, Europe is struggling with its dependence on Chinese exports that expose it to coercion, industrial disruption, and geopolitical pressure.

China’s image as a simple source of profit for superior European companies has faltered. The loudest consternation comes from the EU’s industrial hub, Germany. Its car manufacturing industry has initially been boosted by an expanding Chinese market, even leading to companies like BMW setting up factories there as a gateway to the broader Asian market. However, slowing demand in China and an uptick in domestic competition has changed the picture entirely. Now, German car-manufacturers complain of Chinese dumping schemes in Europe, generous state subsidies to Chinese companies, and trade uncertainty over crucial components like chips and critical minerals. The sudden withdrawal of access to rare earths and Nexperia’s chips have made the threat to European industry more explicit.

Europe’s changing strategy

China’s chokehold over Europe is critical, yet not something the EU could not overcome by correcting for an asymmetry in uneven trade regulations between the two entities. For example, China’s original licensing system for seven rare earth elements still operates, enabling it to delay shipments whenever it chooses. Chinese authorities can in practice also restrict exports of many other critical inputs for European industry, such as industrial textiles, spare parts for machinery, and transport equipment among others. To secure rare‑earth licenses, European companies must disclose unusually detailed data on their products, supply chains, and customers — sensitive information they would not normally release. EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen believes the bloc’s ties with China “have reached an inflection point” as the EU’s total trade deficit with China is set to reach a new record of EUR 700 billion in 2026.

Interestingly, the EU has faced a similar strategic dependency in recent years. Not without serious delay and consternation from some of the countries within the bloc, it overcame Russia’s energy hold on the continent by launching REPowerEU in 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. More recently, it committed to a complete phase out of all Russian gas and liquefied natural gas by the end of 2027. This example is significant, considering that the EU imported over 45 per cent of its natural gas and 27 per cent of its crude oil from Russia in 2021. Thus, even large dependencies on strategic goods from geopolitical rivals can be overcome if the political incentives give momentum to rapid economic and investment shifts. Nevertheless, the case of China and its critical minerals is different, because there is some time for a transition that does not have to be as abrupt as with Russia. While China is a geopolitical rival of the EU, it is not actively waging a war of aggression on the EU’s doorstep. Thus, it is clear why the EU’s reaction to Russia was out of a sudden necessity while it has more time to balance its trade with China.

There are steps the EU could take to reduce its dependency on China in the short to medium term. It could place requirements for Chinese companies and their subsidiaries to disclose information on their products if they want to operate in Europe, akin to the rules European companies face when operating in China. Like Japan, the EU could start stockpiling critical minerals and other components to avoid doomsday scenarios where supplies could suddenly stop, as in fact one saw in November of 2025.

If the EU is willing to take an even stronger stance, it could deploy the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI), which would restrict certain critical exports from the EU to China. For example, the EU exports significant amounts of machinery and high-end industrial products which China requires for manufacturing and cannot quickly replace. Therefore, even if the EU were to take more stringent measures as outlined above, China’s willingness to retaliate would essentially be limited. Even if it tried applying export controls or tariffs, the EU’s new retaliatory measures would incur notable costs to its own industry. Hence, coercive economic tools on both sides would provide for deterrence and reduce China’s risk appetite. Due to its volatile relationship with the US, it could also be argued that China is looking towards the EU as a more trustworthy trade partner, given the Union’s strong preference for predictable and calculated economic policy.

Image credit: Unsplash/Kamekichi Photos

Moreover, the industries in which China is superior to its European counterparts include cars, light machinery, metals, pharmaceuticals, and chemicals, while the EU boasts a more bustling service sector and does not predominantly rely on exporting manufacturing goods. Taken together, those manufacturing goods are important industries in only a few European countries, notably the Czech Republic, Germany, and Hungary. Much like Russia enacts its influence over certain Trojan horses in Europe, China cannot force the entire bloc to submit to its economic pressure, instead seeking easy targets like Hungary, which is keen on cooperating with populist or autocratic governments. Hence, the EU Commission’s role becomes crucial: to use the mandate it has been given regarding trade policy and coordinate the bloc’s actions in order to side-step myopic policies of some of its less-prudent member states who might have greater trade exposure to China.

A geopolitical issue beyond trade policy

Some cautious optimism can be voiced given the EU’s ability to overcome similar chokeholds in the past and since its major members have finally begun ringing the alarm bells. What is more concerning, though, are the crumbling alliances and internal disputes which might keep Europeans from standing their ground in their relationship with China. The most recent example of diverging economic interests between the Netherlands and Germany illustrates this issue. The German car manufacturing industry, being highly exposed to Chinese chip imports — for example, from Nexperia — understandably does not share the same views over economic strategic autonomy as the Netherlands. In a similar manner, states like Hungary might bargain for a softer trade policy with China in return for it lifting its veto on other unrelated issues in the EU Council, thus revealing the complex interdependencies in EU politics.

While the US allowed Europeans a short sigh of relief after Trump negotiated a moratorium on the expansion of export controls on rare earths at the end of October 2025, the larger picture shows how the US is making decisions with the EU on the sidelines. This reflects the growing misalignment between the two actors on key global issues, including trade with China, Russia’s war in Ukraine, or competing claims over Greenland. Even though the bloc is directly affected by US and Chinese trade spats — including tariffs that are rerouting global supply chains and increasing Chinese dumping in European markets — it remains isolated in its approach to affect larger trade flows since it does not have the ear of the US president, and the recently published US National Security Strategy does not see Europeans as equal partners in the transatlantic alliance.

China’s dominance in critical minerals and rare earths has, thus, become a central test of Europe’s quest for strategic autonomy and remaining an important geopolitical actor. In a bid to power green and digital transitions, Europe is struggling with its dependence on Chinese exports that expose it to coercion, industrial disruption, and geopolitical pressure. The Dutch Nexperia case highlights how unilateral responses are easily punished by a quick response from China, whereas coordinated EU action could theoretically rebalance asymmetries. Ultimately, reducing this dependency is not about decoupling from China completely, but about building resilience to defend Europe’s security, prosperity, and political agency in an era of economic confrontation.

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed are those of the writer and do not necessarily represent those of the 9DASHLINE.com platform.

Author biography

Kristofers Krumins is currently the project manager at Riga Stradins University China Studies Centre and a masters student at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service studying Eurasian, Russian, and East European affairs. His interests include European security and foreign policy. Kristofers has served as the UN Youth Delegate of Latvia (2024) and remains actively engaged in fostering the debate movement as a board member of the Latvian Debate Association. Image credit: Unsplash/Vishnu Mohanan.