In Dialogue: Universities between China and the West

IN DIALOGUE: UNIVERSITIES BETWEEN CHINA AND THE WEST

11 May 2022

IN DIALOGUE WITH KEVIN CARRICO AND ANDREW CHUBB

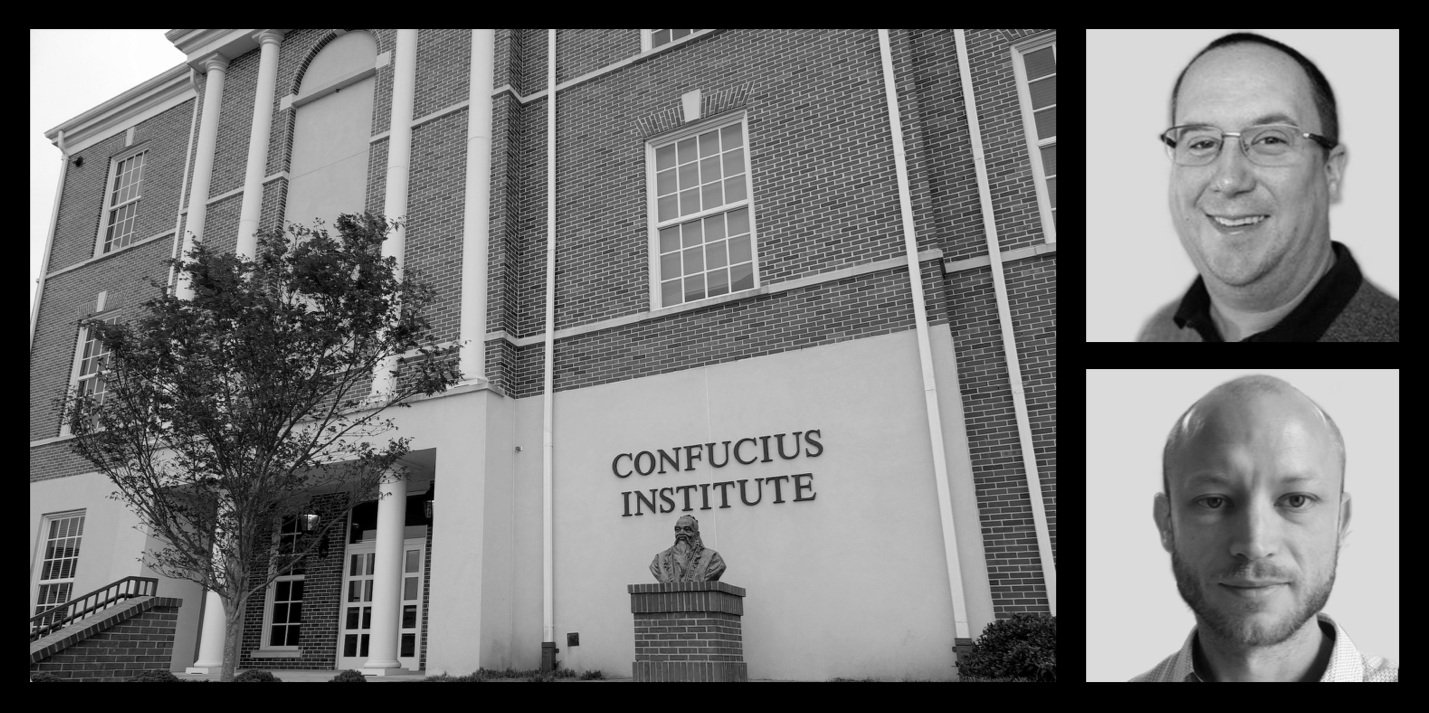

In recent years we have seen many instances of controversy over the mode and extent of Chinese involvement and affiliations in universities across ‘the West’. Since 2019, there have been student protests at the University of Queensland. In Germany, AfD MEPs have asked questions in the European Parliament, and in the UK, guidance was requested (and provided) for dealing with ‘foreign interference’ in universities. There have been many calls to close Confucius Institutes and just recently a Dutch university chose to cut ties with a Chinese funding stream. In short, there is great uncertainty and contention about how to engage in ‘China-West’ academic relations.

In this inaugural edition of 9DASHLINE’s new feature, In Dialogue, we ask two experts the following question: Should ‘Western’ universities reconsider their ties with Chinese research and funding organisations?

Over the past few decades, universities have raced to build research ties with Chinese universities, establish joint campuses in China, or set up Confucius Institutes. Such ties with a regime like the CCP were deeply problematic from the start. Although premised on the optimistic idea that intellectual engagement and exchange might encourage greater freedoms in China, in reality, these links always ran considerable risk of doing precisely the opposite, by legitimising and even encouraging reliance on a system fundamentally hostile to basic freedoms on a global scale.

For the sake of maintaining and nurturing partnerships, research access, and the lucrative financial benefits derived therefrom, academics and administrators in open (and admittedly imperfect) societies might shy away not only from controversial discussions of China’s reality but indeed from honest discussion entirely. That honest discussion can be perceived as somehow dangerous is precisely the crux of the problem. With the PRC’s shift over the past decade from already quite unpleasant authoritarianism to what can only be characterised as full-on fascism under Xi Jinping, these problematic relationships have only become ever more unjustifiable and now need to be placed in the dustbin of history.

Are we really comfortable with collaborations that give an air of legitimacy to the conscious watering down of human rights, to baseless COVID-19 conspiracy theories, to the latest mind-numbing Institute for Xi Jinping Thought that facilitates the unfolding genocide in East Turkestan in which millions are held in concentration camps solely on account of their ethnicity, that aid and abet Russian war crimes in Ukraine that repeatedly justify the invasion of the democratic nation of Taiwan through an anachronistic myth of racial homogeneity? Or has the time come to no longer be accomplices to the crimes unleashed by the CCP against the former Qing Empire’s diverse peoples.

Might our energies be better redirected toward a project of taboo-free and joyfully subversive thinking about the ideas of China and the ‘China model’, to promote the freedom and independence of these nations? Might such a reoriented vision of international exchange better serve the academic project of genuine thinking against a neoliberal model of for-profit engagement with a determinedly anti-liberal regime?

In a word, universities should absolutely reconsider their ties with the PRC in light of its increasing authoritarianism and worsening human rights situation at home. Alongside the various reasons Kevin has already provided I would add that some PRC research funding sources may be directly complicit in, or even profiting from, extreme repression inside China and elsewhere; that collaborative research in computing and artificial intelligence could contribute to the development of high-tech tools of surveillance; and that many partnerships suffer(ed) the erosion or suspension of the principles of academic freedom.

I also share Kevin’s dismay at the neoliberal ‘enterprise university’ model and its failure to grapple with the ethical, political, and security problems that the PRC has presented. But I don't think this is the whole story of Sino-foreign engagement in higher education. Various linkages between ‘Western’ and Chinese researchers and institutions may be benign, beneficial, or even vitally important in light of existential global challenges like climate change.

Kevin rightly asserts the need to oppose and roll back collaborations that lend legitimacy to PRC crimes and propaganda lines. Doing so, however, requires methodical consideration of which collaborations and partnerships are actually doing that. It is not immediately obvious why continuing joint research on, say, wind power, or pollution control measures, would give legitimacy to the Xinjiang genocide, or threats and intimidation against Taiwan. The practical question that should guide universities’ reconsideration of their China ties is not whether to engage, but in what areas, in what form, to what degree, and with what institutional safeguards.

I’d also quibble with Kevin’s claim that the PRC under Xi ‘can only be honestly characterised as full-on fascism’. As a student of Chinese politics, I also find the totalitarian impulses of Xi’s ‘New Era’ hard to miss, and as a Sinophile, it's deeply distressing. But the notion that anyone who thinks or argues otherwise is failing to be ‘honest’ exemplifies, in my view, the degeneration of our public debates on China policy in recent years. I'd argue public policy discussions on China should focus on disaggregating the specific problems the PRC poses for liberal institutions, and on debating the merits of various practical measures to protect them.

I am glad to see Andrew agree that universities need to reconsider their relationships with China on account of the dire political situation there. Our main point of disagreement would appear to be the extent of such reconsideration. Whereas I call for total disengagement from the PRC, to avoid supporting and legitimising a regime engaged in crimes against humanity, Andrew points out that some academic linkages with Chinese institutions may be benign, beneficial, or even vitally important in light of existential global challenges like climate change.

This sounds plausible, and I know many people who agree. But, in my reading, this is a new iteration of what James Mann has called ‘the China fantasy’: the hope that something redeeming or even potentially progressive might emerge from cooperation with a state enacting genocide, beyond this state’s self-legitimising and self-perpetuating goals.

Frankly, the problem with this hope is that any other state engaged in crimes on the scale of today’s CCP would be a pariah in the international community. The question that China scholars concerned about human rights should ask is not how we might tweak research collaboration with a genocidal state ever so slightly, but rather how and why the CCP perpetually escapes this fate of being a pariah state. Do we, for example, collaborate on wind power research with Russia as it slaughters civilians in Ukraine? Do we work on health logistics with North Korea? If not, then why do we feel so reliably comfortable and confident collaborating with the PRC today?

Finally, I would disagree with Andrew’s assertion that my comments on fascism in China reflect the ‘degeneration of public debates on China policy’. Various soft euphemisms have been used even in critical discussions of the CCP model in recent decades, from ‘authoritarian’ to ‘nationalist’. None of these, however, even begin to accurately reflect what we see on the ground today in Xi’s China. Developments in both Russia and China in recent years have demonstrated how soft-pedalling language has led to glaring misperceptions of the acts of which these states are all too capable. The increasingly discomfiting realities of the CCP regime today can only begin to be honestly expressed through more deeply discomfiting language that forces us to confront these realities head-on.

There’s a huge difference between Jim Mann’s ‘China fantasy’ of economic engagement inevitably transforming the PRC’s political system and the belief that particular kinds of research collaboration with the PRC might be beneficial or even necessary to humanity as a whole. Kevin’s position that no collaboration can lead to a positive outcome, regardless of the issue area, circumstances or conditions, is an equal and opposite China fantasy. Take climate change. Given the PRC’s contribution to global carbon emissions is the world’s largest, how are the massive greenhouse gas reductions we require supposed to be realised without cooperation with the PRC? Do we trust the CCP to take care of cutting China’s emissions unilaterally, once Western scientists sever all ties with their Chinese partners?

Kevin’s right that many other states that commit atrocities make themselves international pariahs — except of course when they’re important allies of our own governments. But just as political exigency counts for something in international politics, sheer size and capabilities count in areas like science. Kevin’s hypothetical examples of collaboration with Russia and North Korea are useful: if Russia was a key player in wind power rather than a leading source of fossil fuels, or if North Korea was investing massively in tackling the problems of an ageing population, then there would be much stronger rationales for cooperation with those states in such areas.

It’s true that cooperation would offer no comfort to the victims of CCP repression, but neither would higher Chinese greenhouse gas emissions. Arguing against a disaggregated approach to research collaboration, Kevin points out that, given the PRC’s resistance to basic principles of human rights and dignity, ‘cooperation cannot be easily bracketed off into distinct fields’. That’s true, but coming up with easy answers is not what disaggregation is about. On the contrary, methodically reassessing which collaborations are beneficial enough to persevere with, and under what conditions, requires hard work, hard thinking, and hard choices.

The fundamental question is: does research on admittedly genuine and pressing global issues like global warming require working with a state actively engaged in genocide? Would an Uyghur arbitrarily held in a concentration camp, forcibly separated from their children and facing inhuman treatment on a daily basis, find comfort in international research collaboration on wind power with universities funded and controlled by the same regime that has destroyed so many lives?

In an era in which the PRC government has shown its determined resistance not only to political reforms but to basic rights and dignity, cooperation cannot be quite so easily bracketed off into distinct fields — particularly when cooperation feeds into a fully state-controlled system dedicated to the suppression of citizens, the genocide of minorities living under colonial occupation, and imperialist invasion of neighbouring democracies.

There’s no doubt that soft-pedalling language that lessens the CCP’s crimes is a problem in the corporate world and in the university sector, and deserves to be called out. But the idea that it’s self-censoring to engage in debates about the nature of the CCP regime on any terms other than “fascist” is hard to fathom. There are important debates underway over the comparison of today’s CCP regime to earlier totalitarian states like Nazi Germany and the USSR. But the answer isn’t simple; there are disturbing similarities — certainly enough to sustain an argument that the PRC today is fascist — but there are also differences.

Similarly, on policy questions such as the one we’ve been discussing here, I think a productive debate will focus on what kinds of cooperation are beneficial or necessary, particularly in the context of the existential environmental crisis our species is facing, the specific issues that are posed by the PRC and its current policies and practices, and the merits of various solutions, strategies and countermeasures.

DISCLAIMER: All views expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily represent that of the 9DASHLINE.com platform.

Author Biographies

Kevin Carrico is Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies at Monash University. He is the author of Two Systems, Two Countries: A Nationalist Guide to Hong Kong (2022) and The Great Han: Race, Nationalism, and Tradition in China Today (2017), both published by University of California Press. He is also a former columnist for Hong Kong's Apple Daily.

Andrew Chubb is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at Lancaster University, researching the relationship between domestic public opinion and international politics in East Asia. His recent publications include the RUSI Whitehall Paper, PRC Overseas Political Activities: Risk, Reaction and the Case of Australia (Routledge, 2021), and the KCL Lau China Institute policy brief, ‘Rights Protection: How the UK Should Respond to the PRC's Overseas Influence’. Image credit: Wikimedia/Kreeder13.